| Return

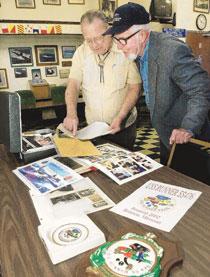

Life Beneath the waves Members of new veterans group remember intensity of "silent service" By Eric Eckert Article date: Oct. 17, 2002 Copied from: OZARKNOW - News-Leader Paul Ingalsbe can still feel the numbing chill of the icy Arctic waters that engulfed him and almost took his life 53 years ago. "The temperature was about 46 degrees," said Ingalsbe, 75, of Springfield. "You could only last for about 10 to 15 minutes before you lost ability to move yourself ... I was just treading water to keep my head up." Ingalsbe was one of 12 men on the USS Tusk --- a submarine operating in the frigid waters north of Finland --- swept overboard Aug. 25, 1949, while attempting to rescue the crew of the drifting USS Cochino. Seven of the men thrown from the vessel by a towering wave died that morning. Ingalsbe survived by grasping frantically at a line in the raging sea. "I remember I was wearing two pairs of gloves," the veteran said. "I slid down the line and grabbed hold of a knot. I was being drug along through the water along the sub." His shipmates eventually pulled him to safety. Several of the bodies were never recovered. Ingalsbe told that story Tuesday to

several members of the Ozark-Runner Base, a chapter of the national U.S.

Submarine Veterans Inc. About 30 men throughout the region have joined

the new group, which was formed in April and based in Springfield.

"The only requirement," said treasurer Garth Greene, "is that anyone who becomes a member has to be qualified on submarines. "Our main purpose is to promote submarine service and memorialize those people who were lost in World War II," Greene added. "Fifty-two submarines with full crews were lost in that war. In peacetime, weíve lost a total of 15 submarines." While the men gathered Tuesday never served on the same boat with each other, they all have a common bond --- a kinship shared only by those qualified to serve their country in the depths of the oceans. "If you go some place and find out thereís a submariner there, thereís automatically a new friendship," said retired navigator George Poddig, 63, who served on both diesel and nuclear subs from 1957 to 1976. "Itís just a different life." The majority of the groupís members are retired. They gather often to reminisce and share their stories. Sometimes they forget the minor details, but they always remember the intensity of the "silent service" --- living a life beneath the waves, where survival hinged on split-second reactions and sometimes their ability to hold their breath and swim to safety. "You had to pass some pretty tough tests to qualify," Ingalsbe said, a slight grin smoothing the wrinkles on his face. "You had to hold your breath for two minutes and you had to pass a whole series of physical tests." "Everybody had to see a head-shrinker, too," added Greene, prompting a stifled giggle from those stationed around the table. Tinsley served in the Navy from 1935 to 1955. He worked as an engine man chief on various subs during his tenure. The veteran said he joined the Navy for the pay and to meet women. "I was making 75 cents a day hoeing cotton in Arkansas," he said. "One day I was out in the field and saw my next-door neighbor --- who was in the Navy --- drive by in a red convertible with a bunch of girls on the rumble seat. Thatís when I told my sister, ĎIím gonna join.í" Submariners experience a life of adventure --- and danger. In the older subs, sailors were subject to problems such as gas leaks, fires and mechanical failures. "You had to know every pipe that ran through that thing and you had to know how to fire a torpedo," Tinsley said. "You needed to be able to do everything in case something went wrong or there was an emergency." Aside from the dangers, many felt submarines were safer than the top-water vessels. "We always said there were two types of ships --- submarines and targets," Poddig said, citing an old submariner adage. Often submerged for months at a time, submariners learn to adapt to cramped spaces and the loss of top-water luxuries --- including fresh air. "It could get pretty stale down there," said John Middlemas, 82, who served on numerous subs during World War II. "Older subs didnít have air conditioning. Fresh air was a premium anytime you could get it." Greene said sailors often had to find ways to pass the time. "In the evening, one of the big things was movies," he said. "Sometimes youíd see the same ones several times. There was also a lot of reading, study and work in the off time ... When youíre at sea, youíre always in alert mode." Middlemas said the camaraderie on a submarine was exceptional. "Itís about as close to Christianity as you can get without being Christian," he said. "You love Ö everybody." |